Academics make stronger connections between gum disease and Alzheimer’s disease

Researchers at the School of Dentistry, University of Central Lancashire (UCLan) were the first to report the link between gum disease and Alzheimer’s disease.

Now two new studies from the same research group at the School of Dentistry demonstrate that progress is being made in making much stronger connections between gum disease in the mouth and deteriorating brain function.

The studies are incredibly timely, as September is the World Alzheimer’s month and September 21 is World Alzheimer’s day. Marking this important awareness day, the two new studies—published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease Reports, respectively—give a better understanding of the defining Alzheimer’s disease lesions on the brain: technically known as amyloid-beta plaques and neurofibrillary tangles.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common type of dementia, progressively causing deterioration of memory, thinking skills and the ability to communicate. The exact cause of this disease is not yet fully understood, which means it’s a difficult disease to prevent and treat.

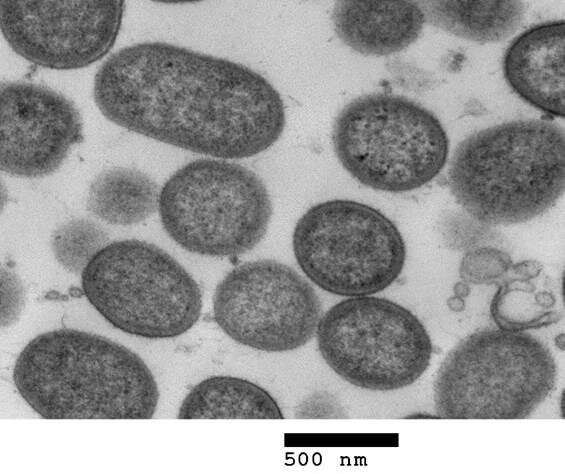

It has been previously shown that the Porphyromonas gingivalis bacterium which destroys gum tissue—and the enzyme which it produces, known as gingipains—are specifically linked to Alzheimer’s disease, after both were discovered in the brain tissue of those suffering from the disease. These new studies go a step further in exploring how gum disease and its bacterial proteins can potentially contribute to the formation of lesions on the brain.

The first study, to be published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, shows that nerve cells in the brain contain a type of protein called tau. When tau meets the gingipains enzyme, the tau released from the nerve cell. Once freed, tau physically changes, in the form of coils and non-coiling filaments. These filaments of tau then re-attach to the nerve cell and become incorporated into the lesion known as neurofibrillary tangles. These ultimately kill the nerve cells.

What this means is that once a nerve cell dies and the free tau protein leaks into the brain, the tau may attach itself to healthy neighboring nerve cells, repeating the process and leading to further damage to the brain as the disease spreads.

The second study, published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease Reports, looks at the way the gingipains enzyme, released by the bacterium, can contribute to the formation of amyloid-beta plaques—another of the lesions, alongside the tangles, which form on the brains of those suffering from Alzheimer’s.

These studies are small steps in the fight against Alzheimer’s, but the results are significant in understanding the role of gingipains and how fundamental they are to lesion formation. It is hoped that studies such as these will help with developing future treatments.

Source: Read Full Article