COVID-19's long-term effects on chemosensory functions

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which is the virus responsible for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has been found to cause olfactory dysfunction (OD) in approximately 60% of infected patients. In addition to OD, other common indicators of COVID-19 include fever, cough, or shortness of breath.

Study: COVID-19 Has Long Term Effects on Chemosensory Functions. Image Credit: DimaBerlin / Shutterstock.com

Study: COVID-19 Has Long Term Effects on Chemosensory Functions. Image Credit: DimaBerlin / Shutterstock.com

Studies investigating the long-term effects of COVID-19 on chemosensory function have been limited for several reasons including small sample sizes, unclear diagnosis of the infection, or self-assessment by those with hyposmia, which is defined as a partial loss of smell. As a result of these limitations, further analysis for the prevalence of OD and other alterations in chemosensory functions must be conducted.

To this end, a group of Canadian researchers has recently conducted a comprehensive study investigating the long-term effects of COVID-19. These long-term effects included olfactory and gustatory symptoms, as well as trigeminal alterations that affect smell, taste, and motor functions in the face. The results of their study were recently published on the preprint medrxiv* server.

The study

The researchers of the study analyzed questionnaire responses from a sample of 704 healthcare workers with confirmed COVID-19 infections during the first wave of the pandemic that occurred between February 2020 to June 2020. The team of scientists also developed a test for assessing chemosensory functions known as the Chemosensory Perception Test (CPT). The CPT utilized household items such as deodorants and tastants to ensure that the self-evaluation of these symptoms by the participants was both easy and accurately assessed.

The purpose of the CPT was to evaluate the extent of the olfactory and gustatory senses of the participants, with odor intensity being the best indicator of any dysfunction in these senses. The participants of the study were asked to self-assess their olfactory, gustatory, and trigeminal sensitivity using a 10-point visual analog scale.

The participants were also asked to assess their chemosensory symptoms on three time points, which consisted of prior to the SARS-CoV-2 infection, during the infection, and at the point of completing the questionnaire for the study. The participants were also asked to provide any information on the presence of parosmia, which is defined as abnormalities in smell, or phantosmia, which occurs when patients may experience imaginary odors. Any alterations to tastes were also recorded, with all five tastes of sweet, salty, bitter, sour, and umami being included.

Study findings

Over half of the study participants who had recovered from the acute phase of COVID-19 reported an olfactory loss for 3-7 months after their infection. Therefore, this finding affirms that this symptom can continue post-infection and not return to baseline for an extended period of time. A loss of gustatory senses was also similarly reported in approximately 40% of patients who reported continual gustatory sensitivity for a median of 4.8 months post-COVID-19 infection.

Approximately 10% of participants also reported experiencing either parosmia and/or phantosmia. Notably, a disproportionate number of women were affected by these long-term symptoms of COVID-19 compared to men.

Olfactory and gustatory changes

The researchers found a moderate to strong correlation to exist between olfactory and gustatory changes which were reported by the participants, as compared to trigeminal changes. This may be due to the similarity of the pathophysiological pathways of these senses.

Another explanation for this correlation included the limited ability of these individuals to discern between taste and retro-olfaction. More specifically, the participants may have found it difficult to distinguish the sense of taste in the mouth from retro-olfaction, which consists of odors from substances in the mouth traveling to the olfactory epithelium.

When investigating the gender bias of more women having chemosensory symptoms post SARS-CoV-2 infection as compared to men, the study found that women tended to score higher in olfactory testing. This finding may indicate that women might exhibit a higher rate and persistence of OD after COVID-19 because of the presence of different endocrine, social and cognitive factors.

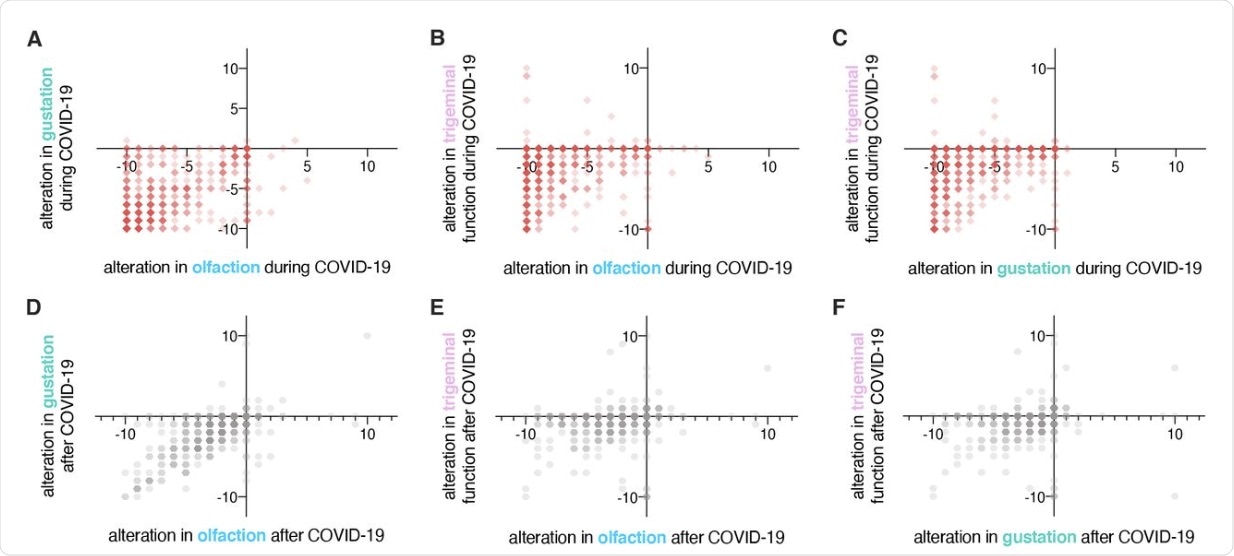

Correlations between alterations in chemosensory modalities (n=704). Red squares, correlations between alterations in olfaction, gustation, and trigeminal functions during COVID-19. Grey hexagons, correlations between alterations in olfaction, gustation, and trigeminal functions after COVID-19. Darker colors indicate higher occurrence.

Correlations between alterations in chemosensory modalities (n=704). Red squares, correlations between alterations in olfaction, gustation, and trigeminal functions during COVID-19. Grey hexagons, correlations between alterations in olfaction, gustation, and trigeminal functions after COVID-19. Darker colors indicate higher occurrence.

The effect of OD

The long-term symptoms of COVID-19 discussed here can have long-lasting effects that may impact the quality of life for patients who have recovered from COVID-19. Both parosmia and phantosmia, for example, are considered qualitative smell disorders that can involve unpleasant olfactory sensations such as smells like rotten eggs or sewage. While the pathological mechanisms responsible for these disorders remain unclear, parosmia may be associated with altered peripheral input or central processing of an olfactory stimulus.

The presence of chemosensory changes can also impair the ability of these patients to enjoy food, which can be distressing for some individuals. In fact, a lack of olfactory sense has even been associated with higher rates of anxiety and depression.

Additionally, the effect of anosmia can prevent individuals from ascertaining harmful substances such as gas or expired food. It can also lead to dysfunctional nutrition, with individuals consuming a higher intake of salt or sugar in their diet, which can result in unhealthy eating disorders like anorexia.

Olfactory senses can also be important for some occupations where staff are required to be able to smell urine, excrement, or infected wounds. Therefore, any alterations in these senses may compromise the ability of these individuals to complete their jobs to the best of their abilities.

Conclusion

The study concluded that due to the regenerative ability of olfactory epithelial cells, it is possible for the olfactory sense to regain function. This remained true in the current study, wherein 75-85% of infected participants recovered their olfactory sense within 60 days. However, continual chemosensory dysfunction may be due to chronic central nervous system changes, which the researchers mention can occur through the ability of SARS-CoV-2 to infect olfactory neurons in humans.

There is currently no approved therapy for COVID-19 OD; however, olfactory training, which is often used after other viral infections, may also be useful for those experiencing the same symptoms after recovering from COVID-19.

*Important notice

medrxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

- Bussiere, N., Mei, J., Levesque-Boissonneault, C., Blais, M., et al. (2021). COVID-19 Has Long Term Effects on Chemosensory Functions. doi:10.1101/2021.06.28.21259639. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.06.28.21259639v1.

Posted in: Medical Science News | Medical Research News | Medical Condition News | Disease/Infection News | Healthcare News

Tags: Anorexia, Anosmia, Anxiety, Central Nervous System, Chronic, Coronavirus, Coronavirus Disease COVID-19, Cough, Depression, Diet, Endocrine, Fever, Gustatory, Healthcare, Nervous System, Neurons, Nutrition, Olfaction, Pandemic, Respiratory, SARS, SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, Syndrome, Virus

Written by

Marzia Khan

Marzia Khan is a lover of scientific research and innovation. She immerses herself in literature and novel therapeutics which she does through her position on the Royal Free Ethical Review Board. Marzia has a MSc in Nanotechnology and Regenerative Medicine as well as a BSc in Biomedical Sciences. She is currently working in the NHS and is engaging in a scientific innovation program.

Source: Read Full Article