Leonardo da Vinci: Visionary Anatomist, Imaging Pioneer

AMBOISE, France — Beyond being a gifted painter, a skilled inventor, and a talented engineer, Leonardo da Vinci was also an avid researcher with an insatiable curiosity who sought to unravel all the mysteries of the human body. In an exhibition this summer, visitors are invited to learn about this brilliant pioneer of anatomy and discover the origin of modern dissection techniques. And what better venue than the Château du Clos Lucé, where the man who so masterfully joined together art and science spent his final years? Dominique Le Nen, MD, a university professor and surgeon at the Regional University Hospitals of Brest, France, and Pascal Brioist, PhD, professor of modern history at the University of Tours, France, designed a path along which visitors can take in the life of Leonardo, visionary anatomist and precursor of modern imaging.

Art Meets Science

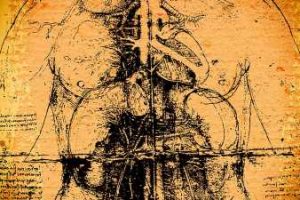

The exhibition traces 30 years of one man’s relentless quest to solve the mystery of life. Any discussion about deciphering the human body — its mechanics, its movement, the functions of its organs — must include the anatomic studies carried out by Leonardo, studies meticulously presented in scientifically rigorous and esthetically revolutionary ways in his writings. Although he was not a physician, Leonardo developed innovative dissection techniques, proceeding in layers or sections or in views around object (a sculptor’s method) before presenting everything together as a whole.

Throughout his life, he corresponded with numerous physicians and performed dissections in various hospitals. From 1500 to 1507, he was in Florence, Italy, at the Santa Maria Nuova Hospital. There, he worked alongside Antonio Benivieni and Andrea Cattaneo, learning all he could from their medical expertise. In 1508, he collaborated with anatomist Marcantonio della Torre (1481–1511) at San Matteo Hospital in Pavia and the Ca’ Granda Hospital in Milan.

Brioist pointed out that, contrary to popular opinion, Leonardo did not carry out his dissections in secret but “in hospitals, and in complete agreement with the political and religious authorities.” As evidence of this, it is known that sometime around 1515, he was in Rome. He regularly visited with the Pope’s doctor, Francesco Dantini. In addition, Leonardo could be found at two of the city’s hospitals, Santa Maria della Consolazione and Santo Spirito, where he continued his research into anatomy. His materialistic ideas about embryology did, however, incur the Pope’s wrath, for, as Brioist explained, Leonardo believed that at conception, the fetus’ soul came from the mother, not from God.

Leonardo was far from being satisfied with descriptive anatomy: he had a pressing need to understand how the human body worked. It was this need that drove the Tuscan master to come up with new methods of dissection. As Brioist put it, “Other artists stayed on the surface. Leonardo dove into the depths.”

Before MRI and CT

According to Le Nen, layered dissection began with Leonardo. This technique is characterized by removing successive strata that make up a body part to get an accurate picture of its anatomic structure. One might do this on, for example, the palm of the hand.

As early as 1487, Leonardo had dissected a human leg, sawing it into cross sections. He was then able to illustrate his findings in a series of drawings: a slice slightly angled, with details showing the muscle compartments separated by walls around the femur, also presented in cross section. “Leonardo thought in 3D,” Le Nen noted. “He was five centuries ahead of the images that we get today using CT scans and MRIs, the kind of imaging where it’s possible to view slices — frontal, sagittal, et cetera. Of course, modern technology is far more advanced, allowing us to reconstruct images in different planes, model them, and animate them in three dimensions.”

Artist-Anatomist

In a multiplicity of anatomic views, Leonardo displays a dynamic — and thus modern — take on the human body. This can be seen in two plates that show a series of eight figures depicting the muscles of the shoulder, arm, and neck. “This series of drawings of the shoulder, around which Leonardo seems to be circling in the different planes of space, takes us back to the approach that the Renaissance artists, in particular, Michelangelo, will advance,” Le Nen said. “In other words, taking preliminary drawings and, from these, making clay models — modelli, as they’re called in Italian — and then producing full-scale sculptures.”

The polymath established yet another innovation, this one based on the idea that the human body could be viewed as a machine made up of “detachable parts and pieces” (think of a toy construction set). So, Leonardo began to remove certain structures to gain a better understanding of how they worked. The exhibition has a reproduction of a sketch in which Leonardo has “drawn out” the clavicle. The lines connecting the bone’s extremity to its normal position reflect his guiding principle of taking away so as to better reveal the underlying structures. “With today’s technology, we can dim specific parts of the anatomy, even make them disappear, so that we can get a better look at other ones. The subtraction technique: Leonardo used it, and now the 3D scanner does,” Le Nen explained.

He went on to say that visitors to the Leonardo exhibition will have the opportunity to view a truly exquisite plate. It’s called “The Vertebral Column.” “No one has depicted the spine any better than that.”

An Unpublished Work

There is an astonishing amount of handwritten documents that clearly show that when it came to anatomy, Leonardo studied it all. Vertebrae, brain, joints, the urinary system, the ventricles of the heart. Men’s bodies, women’s bodies, children’s bodies…. Yet, strangely enough, not many people know that he devoted close to 30 years — almost half his life! — to studying the human body.

Though he intended to publish his work during his lifetime, that never came to pass. After Leonardo died, the vast collection of documents covering his monumental work had to be gathered together, including his countless drawings, sketches, and handwritten notes. Not to be forgotten: Leonardo used mirror writing. The daunting task fell to his disciple, Francesco Melzi. One of the items, containing Leonardo’s anatomic plates, was acquired in 1690 by the Royal Library of Windsor Castle in London. To this day, these plates belong to the British Crown. Excellent facsimiles of many of these have been produced, benefiting experts and novices alike. These pieces are on display at the exhibition.

From studying superficial anatomy and reading the works of Galen to dissecting cadavers at the turn of the 16th century, Leonardo da Vinci carried out pioneering work that led him to become one of the most important contributors to the science of anatomy during the Renaissance. This little-known side of the polymath’s life is on view at the Château du Clos Lucé, where an educational and multidisciplinary journey can be taken through a collection of books dating from Leonardo’s lifetime, as well as facsimiles, anatomic models, dissection instruments, installations, and animated 3D video. A dissection room has also been recreated as part of the exhibition.

This article was translated from the Medscape French Edition.

Source: Read Full Article