Researchers develop gene therapy for rare ciliopathy

Researchers from the National Eye Institute (NEI) have developed a gene therapy that rescues cilia defects in retinal cells affected by a type of Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), a disease that causes blindness in early childhood. Using patient-derived retina organoids (also known as retinas-in-a-dish), the researchers discovered that a type of LCA caused by mutations in the NPHP5 (also called IQCB1) gene leads to severe defects in the primary cilium, a structure found in nearly all cells of the body. The findings not only shed light on the function of NPHP5 protein in the primary cilium, but also led to a potential treatment for this blinding condition. NEI is part of the National Institutes of Health.

“It’s so sad to see little kids going blind from early onset LCA. NPHP5 deficiency causes early blindness in its milder form, and in more severe forms, many patients also exhibit kidney disease along with retinal degeneration,” said the study’s lead investigator, Anand Swaroop, Ph.D., senior investigator at the NEI Neurobiology Neurodegeneration and Repair Laboratory. “We’ve designed a gene therapy approach that could help prevent blindness in children with this disease and one that, with additional research, could perhaps even help treat other effects of the disease.”

LCA is a rare genetic disease that leads to degeneration of the light-sensing retina at the back of the eye. Defects in at least 25 different genes can cause LCA. While there is an available gene therapy treatment for one form of LCA, all other forms of the disease have no treatment. The type of LCA caused by mutations in NPHP5 is relatively rare. It causes blindness in all cases, and in many cases it can also lead to failure of the kidneys, a condition called Senior-Løken Syndrome.

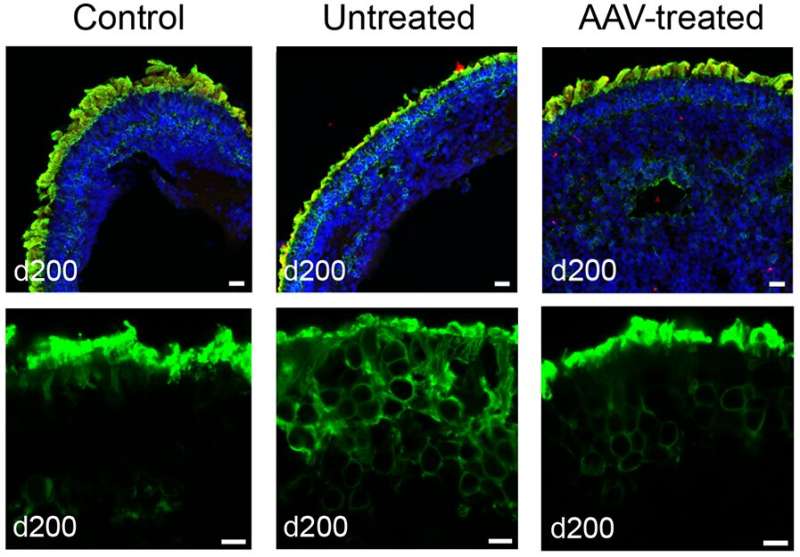

Three post-doctoral fellows, Kamil Kruczek, Ph.D., Zepeng Qu, Ph.D., and Emily Welby, Ph.D., together with other members in the research team collected stem cell samples from two patients with NPHP5 deficiency at the NIH Clinical Center. These stem cell samples were used to generate retinal organoids, cultured tissue clusters that possess many of the structural and functional features of actual, native retina. Patient-derived retinal organoids are particularly valuable because they closely mimic the genotype and retinal disease presentation in actual patients and provide a “human-like” tissue environment for testing therapeutic interventions, including gene therapies. As in the patients, these retinal organoids showed defects in the photoreceptors, including loss of the portion of the photoreceptor called “outer segments.”

In a healthy retina, photoreceptor outer segments contain light-sensing molecules called opsins. When the outer segment is exposed to light, the photoreceptor initiates a nerve signal that travels to the brain and mediates vision. The photoreceptor outer segment is a special type of primary cilium, an ancient structure found in nearly all animal cells.

In a healthy eye, NPHP5 protein is believed to sit at a gate-like structure at the base of the primary cilium that helps filter proteins that enter the cilium. Previous studies in mice have shown that NPHP5 is involved in the cilium, but researchers don’t yet know the exact role of NPHP5 in the photoreceptor cilium, nor is it clear exactly how mutations affect the protein’s function.

In the present study, researchers found reduced levels of NPHP5 protein within the patient-derived retinal organoid cells, as well as reduced levels of another protein called CEP-290, which interacts with NPHP5 and forms the primary cilium gate. (Mutations in CEP-290 constitute the most common cause of LCA.) In addition, photoreceptor outer segments in the retinal organoids were completely missing and the opsin protein that should have been localized to the outer segments was instead found elsewhere in the photoreceptor cell body.

Source: Read Full Article