Setting trans fat limits in Kenya could save thousands of lives and cut costs

Thousands of deaths and heart attacks could be prevented—and billions of Kenyan shillings saved—if the country restricted trans fat in food to World Health Organization (WHO) limits, according to research by the George Institute for Global Health. Findings were published today in BMJ Global Health.

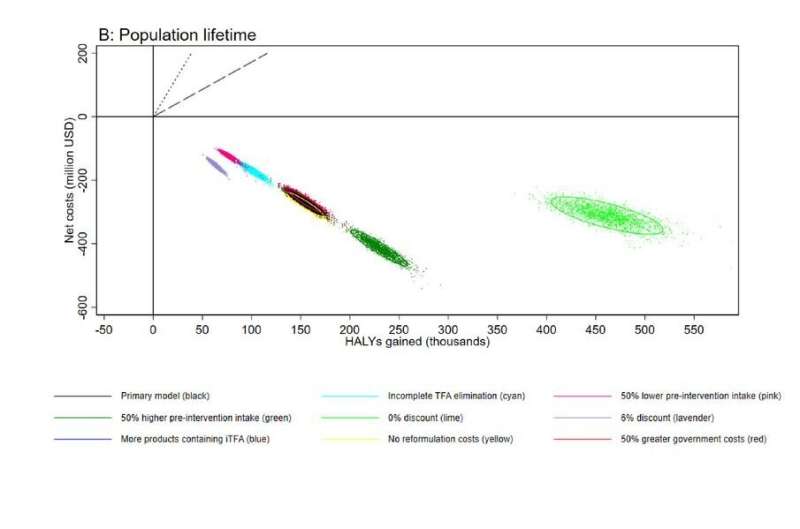

Researchers modeled the impact of limiting industrially produced trans fat to less than 2% of total fats in the Kenyan food supply. Over the first 10 years, the limit would cost the government and food industry approximately 9 million USD (~940 million KES) to implement but would save 2,000 lives and prevent 17,000 cases of heart disease. This could lead to a net saving of 40 million USD (~4.1 billion KES) to the Kenyan health care system.

Lead author and senior research fellow at the George Institute, Dr. Matti Marklund, said, “Our findings show that even in Kenya, where trans fat intakes appear to be relatively low, there could still be significant health and economic benefits to trans fat elimination. Instead of waiting for government mandates, we urge food manufacturers to prioritize consumers’ health now by removing these dangerous fats from products.”

If the trans fat limit recommended by the WHO was mandated in Kenya today, the model suggests approximately 50,000 lives could be saved and over 100,000 new cases of heart disease prevented over the lifetime of the population. For every dollar invested there would be a return of 20 dollars, amounting to net savings of 271 million USD (~28 billion KES).

Industrial trans fats are a group of harmful substances produced during partial hydrogenation, a process where vegetable oils are hardened to solid fats that can be used in processed and fried foods. They are also a well-known risk factor for heart disease but can be substituted with healthier alternatives without affecting food quality.

The WHO lists elimination of industrial trans fat as an effective intervention for the prevention of noncommunicable diseases, like heart disease. The organization says the top two best-practice policies are setting a mandatory limit of 2g trans fat per 100g of total fat in all foods, and a ban on the production and use of partially hydrogenated oils. In 2018 the WHO launched an initiative to help eliminate industrial trans fat globally by 2023.

The death toll from heart disease in Kenya has increased more than three-fold since 1990, a trend mirrored in other African countries. Globally, industrial trans fats are responsible for around 500,000 premature deaths from heart disease every year, mostly in low- and middle-income countries. But only 56 countries have best-practice trans fat policies in place, most of which are high-income countries. Around half the world’s population—approximately 3.7 billion people—are still unprotected by best-practice trans fat policies.

Francesco Branca, director of the department of nutrition and food safety at the WHO said, “The evidence for the benefits of trans fat elimination is strong, but we understand many low- and middle-income countries face implementation challenges and are at risk of being left behind. In Africa, progress has been relatively slow compared to other regions.

“But delays are costing lives, so we’re calling on food manufacturers, the food service sector and suppliers of oils and fats to help plug the gaps where national legislation is not yet in place. Collectively, these companies could have a huge impact on global health. It’s also time to accelerate global policy change on trans fat elimination—millions of lives depend on it.”

Dr. Tom Frieden, president and CEO of Resolve to Save Lives, said “Kenya now has the opportunity to protect its people from this deadly additive, save lives and money, and join South Africa, Egypt and Nigeria as a leader in the drive toward a trans fat free Africa.”

More information:

Matti Marklund et al, Estimated health benefits, costs and cost-effectiveness of eliminating dietary industrial trans fatty acids in Kenya: cost-effectiveness analysis, BMJ Global Health (2023). DOI: 10.1136/bmjgh-2023-012692

Journal information:

BMJ Global Health

Source: Read Full Article