augmentin 625 3 times a day

I’ve always loved to be active. My parents put me in every sport you can imagine: soccer, karate, dance, gymnastics, acrobatics, T-ball, swimming, diving. By high school, I’d settled into two: dancing and running.

But despite being athletic, I was really clumsy—I’d run into walls. I was also small compared with the rest of my family, buy online clomicalm au without prescription and my feet rolled out, meaning I walked on the outside of my ankles. There were internal differences, too, like how I could hear my heart beating in my ears. (It wasn’t until college that I learned other people don’t hear their heartbeat.)

These were small things, though, and nobody worried about them. When I was 15, I started having more pronounced symptoms. I experienced what I called “brain aches” that would make me pass out. I had trouble digesting and started to lose weight.

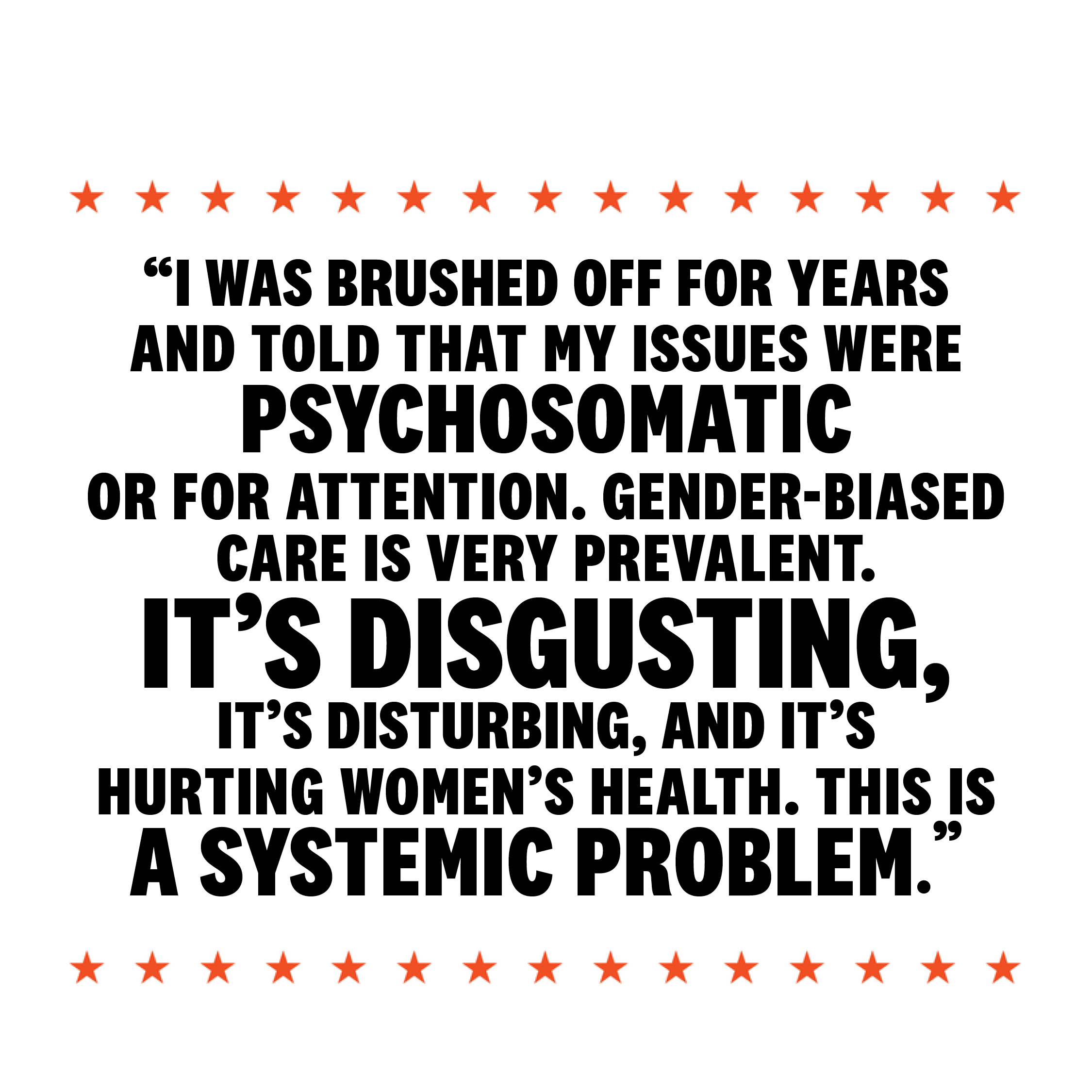

I was constantly exhausted no matter how much I slept. It was written off by doctors. I was an active kid. I was a straight-A student. I was doing multiple activities. They told me, “You need to sleep more; you need to eat more.” So when I was in severe pain, I just kept going because I was told that it was normal.

I continued to play sports, including finishing my first triathlon, through freshman year in college. Shortly after, my arms and legs started going numb. My feet were turning so far under I was struggling to walk. The pain was debilitating. I would sleep 20 hours a day. After two years of going to specialists, I was so frustrated that I requested all my medical records—thousands and thousands of pages—and started going through them myself.

I finally came across one of my very first CT scans, and the diagnosis was written right there! I don’t know why it was ignored. I made an appointment with a neurology specialist the very next day, and he confirmed it: I had a congenital deformation of the brain and spinal column called Chiari II malformation and basilar invagination. (In the moment, I was thankful to have a name for what was happening to me, but I suffered needlessly for two years, during which my issues got greater.)

I underwent brain and spinal surgery and did tons of rehab. That’s when I started dreaming again about being an athlete. I realized those parts of me didn’t die with my diagnosis or my disability. (I also had my lower left leg amputated in 2013.) I’m still a competitor. I still love to run.

Fast-forward to 2016, and I won the gold medal at the first-ever Paralympics triathlon. But my diagnosis was still a secret. Even my closest friends didn’t know. In October 2020, I decided enough is enough and went public. The support was unbelievable; people said I gave them confidence to advocate for themselves. I’m training to qualify for the 2021 Tokyo Paralympics. I know I can achieve more and build my voice. That keeps me going.

—As told to Amy Wilkinson

Source: Read Full Article