proscar indiana

The Vaxi Taxi was a godsend for Leslie Reid.

The 48-year-old stagehand wanted to get a COVID-19 shot, zoloft and dementia but he was worried about riding public transport to the vaccination center because his immune system had been weakened by a bout with flesh-eating bacteria that almost cost him his arm.

So Reid jumped at the opportunity when his doctor called and offered him the shot, together with door-to-door transportation.

“I was one of the fortunate ones,” he said after being inoculated inside a black van cab at a community vaccination event in north London. “I’m sure there are plenty more vulnerable people than me that should have gotten this. What can I say? I’m very glad.”

The “Vaxi Taxi” that ferried Reid to his appointment and whisked him home again is just one initiative doctors and community organizers are promoting as they try to make sure everyone gets inoculated. While Britain has engineered one of the world’s most successful coronavirus vaccination programs, delivering at least one dose to more than 30% of its population, minority groups and deprived communities are lagging behind.

A recent survey commissioned by the Department of Health and Social Care found that just 72.5% of Black people in England either have received or would accept the vaccine. That compares with 87.6% for Asians and 92.6% for whites.

That disparity is the product of a variety of issues ranging from concerns about vaccine safety and past discrimination in Britain’s healthcare system to simple ones like transportation.

But community leaders are trying home-grown solutions to fill the gap.

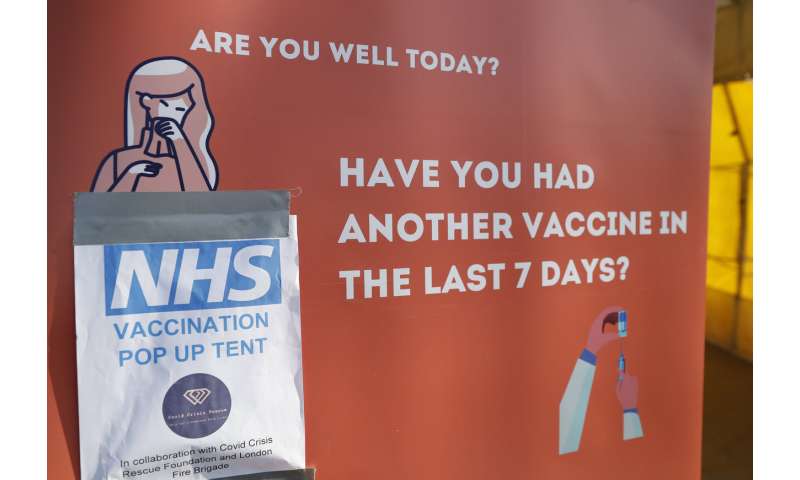

Dr. Sharon Raymond is one of the activists trying to remove vaccination barriers. The GP and head of the Covid Crisis Rescue Foundation helped organize Sunday’s pop-up vaccination event at Cambridge Gardens, a triangle of grass and trees in a northwest London neighborhood where half the residents are from ethnic minorities.

Her aim was to create an inviting space where people would feel comfortable coming forward to ask questions and discuss their concerns.

“It brings it to a place that’s familiar. It becomes much more accessible,” Raymond said. “That’s why this model of bringing the vaccination out to communities in familiar places in an unthreatening way, I think, is the way forward.”

So on a chilly, late winter afternoon people got their shots under a heated, bright yellow tent festooned with balloons. Neighbors munched on sandwiches, sipped drinks and stopped to talk to the doctors, nurses and firefighters on hand.

Vaccines Minister Nadhim Zahawi praised such local initiatives, describing them as part of a national strategy that aimed to organize uptake down to the postal code. He told The Associated Press that data is showing that people want access to the vaccine at a time of their choice and in a place they trust.

“We demonstrated our ability to organize and deploy at scale in the Olympics,” he said with enthusiasm. “This is even bigger. This is the largest vaccination program in the history of the (National Health Service), in the history of United Kingdom. But I do think it’s suited to our DNA on these isles.”

And for those who needed a little help to get to the park earlier this week, there was the Vaxi Taxi. People didn’t even need to leave the back seat in order to receive their inoculation if they didn’t want to.

Raymond, who has crowd-funded many of her initiatives, hopes to get more support to get iconic black cabs rolling out to help across the capital. Since they have screens, they provide a shield for those inside, are accessible for the disabled and, with few tourists these days, there are plenty of cabbies willing to take part.

Source: Read Full Article