In long COVID, blood markers are linked to neuropsychiatric ills

In a new study of long COVID published March 13, 2022, in the Annals of Neurology, UC San Francisco researchers identified biomarkers present at elevated levels that may persist for many months in the blood of study participants who had long COVID with neuropsychiatric symptoms.

The results hold promise for the development of lab tests to gauge long COVID risks and to evaluate new therapies to tackle a form of COVID that has at times been thought of as a subjective syndrome that’s difficult to describe and measure.

“For much of the first year of the pandemic, many people with long COVID were told that what they were experiencing wasn’t even valid,” said Michael Peluso, MD, assistant professor of medicine at UCSF and the first author of the study. “Now, we’re starting to identify objective biological measurements that correlate with what people are telling us about their long COVID symptoms.”

Long COVID is characterized by continuing or newly arising symptoms such as fatigue, shortness of breath, cognitive difficulties, heart rhythm abnormalities, sleep disorders, and muscle and joint pain, that may linger for months after acute infection with the SARS-CoV2 virus.

Researchers estimate that between 10% and 30% of those infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus experience long COVID symptoms (though it appears to be less likely among vaccinated people). Up to 23 million people in the United States already may have been afflicted with chronic health problems triggered by infection, according to a recent report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

Long COVID can even affect individuals who initially experienced only mild disease and perhaps even those who were asymptomatic despite testing positive for infection.

Viral proteins linger in brain cells

To conduct the study, clinicians surveyed 46 previously infected patients about 32 physical long COVID symptoms as well as mental health symptoms such as loss of memory, irritability, agitation, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress and specific sensory losses. In addition, laboratory researchers analyzed blood plasma samples from 12 never-infected control subjects without neuropsychiatric symptoms for comparison.

All study participants were patients in the San Francisco-based Long-term Impact of Infection with Novel Coronavirus (LIINC) COVID-19 study, and were enrolled March 2020 through February 2021, after testing positive for infection. The original intent of the study was to follow patients over time to track natural immunity in the wake of COVID infection, but when it became clear that patients upon return visits were continuing to experience symptoms many weeks after infection, the understanding of these long COVID symptoms became a major focus of the study. The new findings are based on a single time-point, but the patients continue to be monitored for changes in symptoms and immunological and other potential biomarkers.

Blinded to patient identity and symptom status, the team then used a technique based on blood plasma samples—developed by corresponding author, Edward Goetzl, MD, a professor emeritus of medicine at UCSF—to measure viral and patient proteins derived from neurons.

The researchers first isolated protein-filled sacs, called exosomes, released into the blood by all kinds of cells, then selected for only those exosomes derived from neurons and supporting cells known as astrocytes. Goetzl sees this approach as a proxy measure reflecting the disruption that occurs to cells in the brain in the aftermath of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The analysis detected much higher average levels of two SARS-CoV-2 viral proteins they measured—the nucleocapsid protein and the spike protein—in blood plasma samples collected between six and 12 weeks after diagnosis from patients infected with COVID who had neuropsychiatric symptoms in comparison to samples from those who had long COVID, but who did not have neuropsychiatric symptoms. Levels of these proteins from neuronal exosomes in long COVID patients without neuropsychiatric illness were still higher than levels from patients without long COVID.

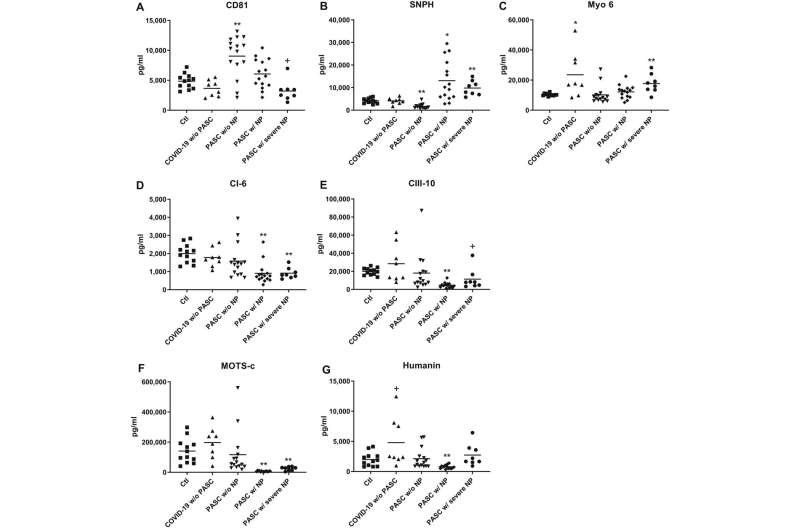

Goetzl said that SARS-CoV-2, like several other viruses, targets structures called mitochondria within the cells it invades. The virus very likely interferes with normal mitochondrial tasks, he said, which include providing the cell with a usable form of energy and contributing to the immune system’s ability to respond to infection. The researchers measured significant differences in levels of several mitochondrial proteins between long COVID patients with and without neuropsychiatric symptoms, pointing to alterations in mitochondrial function within neurons, according to Goetzl.

“I think the majority of scientists who have considered this might say it’s very unlikely that the virus particles remain infectious at this stage, but these viral proteins hanging around in the cell can still do bad things,” Goetzl said. He is optimistic about the development of small-molecule drugs that can enter infected cells and destroy specific viral proteins.

Moving toward diagnosis and treatment

Many researchers attribute chronic symptoms in long COVID primarily to prolonged or altered immune responses, Peluso said. The initial acute infection might trigger long-term, maladaptive changes in the immune system. The ongoing presence of viral proteins within the body might cause chronic inflammatory responses. The presence of certain viral molecules might also trigger autoimmune responses in which the immune system attacks the body’s own tissues.

Source: Read Full Article