‘Yes, And…’: How Improv Can Improve Bedside Manner

When one considers improvisational theater or improv, visions of the scuffed floors of a community theater or reruns of the television show Whose Line Is It Anyway? may come to mind. Images of actors shrugging off inhibitions to embody different characters and scenarios instantaneously, or the desperate attempt not to giggle and break character, are plenty.

When one considers a conversation between a healthcare professional and a patient, the image conjured up is vastly different, more serious, and usually sticks to the medical script. Yet, perhaps surprisingly, healthcare can take a lesson or two from the theatrical technique of improv.

For one physician, integrating lessons he learned from improv into his medical practice yielded incredible results.

“By practicing improv, it has set up a system for developing and evaluating my communication skills, all geared toward connecting with the people I am communicating with,” says Michael P. Smith, MD. Smith is a board-certified internist and an assistant professor in the Internal Medicine Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC), where he’s bringing improv to doctors.

Dr Michael P. Smith is integrating lessons he learned from his improv theater experience into his medical practice.

To Improv or Not to Improv?

In 2014, Smith, like all medical professionals, required a level of bedside manners in order to do his job — and he considered himself to be an “excellent communicator.” That year for Christmas, his wife gifted him a Level 1 Introduction to Improv class at a local theater. He had some friends who do comedy professionally in Chicago, but otherwise had very little exposure to the idea.

“I went to a conference where I told one of my mentors that I was taking improv classes,” Smith told Medscape Medical News. “And he responded, ‘I’m sure that helps you as an academic hospitalist’ to which I replied, ‘Oh yes, for sure…Wait, how do you mean?’ ”

And so the idea of using improv skills to help his work began to percolate in his mind — Does it really help? If so, how can these skills be introduced to others?

Improv is unplanned or unscripted, a form of comedy that relies on the actors’ abilities to riff off one another and create narrative and tension on the fly. The basic rules of improv rely on agreeing with your stage partner no matter what wild scenario or far-fetched line they toss out. If you don’t, there’s very little room to take things further.

When actors do improv, thinking and reacting quickly are necessary to help continue the story that’s being created.

Another more familiar rule is referred to as “yes, and…” You use this phrase when you not only agree with your stage partner, but then add something of your own. People who are familiar with improv believe “yes, and” improves creativity, but there’s more to it than that.

“Improv requires one to go with the flow, to not negate the others’ statements, and to actually respond to what is being said. It asks one to build on an existing premise,” explains Pooja Saraff, PhD, a clinical psychologist at UMass Memorial Health in Worcester, Massachusetts. “If a professional uses improv techniques, they are likely to listen more closely and to reflect back what they hear, in turn validating the patient.”

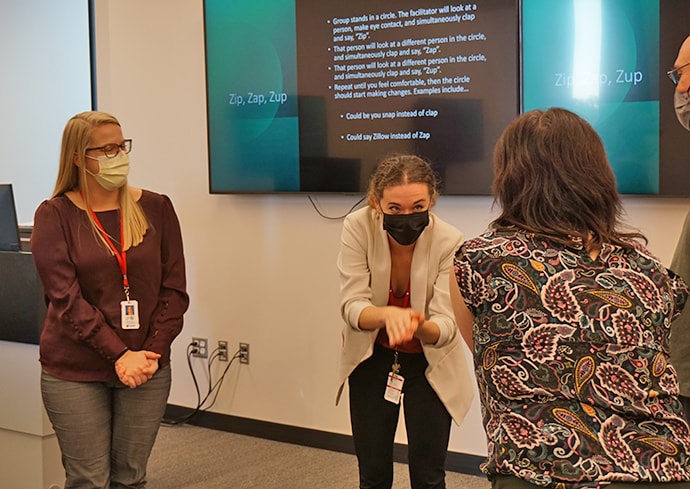

Here, actors play another well-known theater game called “Zip, Zap, Zup,” which requires nearly instantaneous movement between actors.

Saraff explains that when it comes to healthcare, these communication skills are particularly important. Patients look for validation and comfort when dealing with pain and uncertainty regarding their health, and nonjudgmental, respectful communication from healthcare workers can help patients feel like they aren’t just another chart of numbers. Using the “yes, and” technique from improv specifically takes the patient’s view into consideration and doesn’t discount or invalidate any of what they might be feeling or experiencing.

A workshop participant emphatically acts out a scene.

The Impacts of Poor Communication

While good communication can be almost as important as the treatment itself, the reverse is also true: poor communication can be damaging to a patient’s well-being and recovery. Smith was in the process of workshopping his improv exercises in 2017 when he realized just how important these tools could be.

In his immediate family, there was a cancer diagnosis, and then another, and another, until five members of his family had been diagnosed with cancer. And so, for the first time, he found himself on the other side of the doctor–patient dynamic as he accompanied these family members on their diagnosis and recovery journeys.

“I saw several well-intentioned, smart healthcare providers who are great at their job cause harm to my family members by the way that they communicated with my loved ones,” Smith said.

The most damning incident happened with Smith’s sister-in-law, who was told by a nurse her lab results came back “bad.” For the next 2 weeks, Smith’s sister-in-law didn’t go back to the doctor, and instead was trapped in the panic-inducing certainty that “her death was imminent.” When she finally did go back, her doctor told her that her lab results were fine, and moved on from there. It turns out that the labs, while still not healthy, were better than they had been before. But for an ill patient, hearing that “the labs came back bad,” can feel like a death sentence. Smith says that this moment changed his perspective.

At that time, Smith worked on communication exercises with three to six medical trainees once a month. After the incident with his sister-in-law, he said these measures to improve communication “felt woefully inadequate.” It also inspired him to look back on his own abilities. “Thinking back, I am sure there were times where my own communication was inadequate. That has been a main motivator for me. As I developed the improv workshops and activities, I realized [there were] other times where I had, without realizing it, not lived up to my own expectations.”

Creating a Learning Experience

According to Smith, when he pitched the idea of a workshop that introduces improv techniques, people generally fell into three categories: Either they were immediately on board, they thought it sounded fun but didn’t understand the point of using improv, or they just didn’t get it at all.

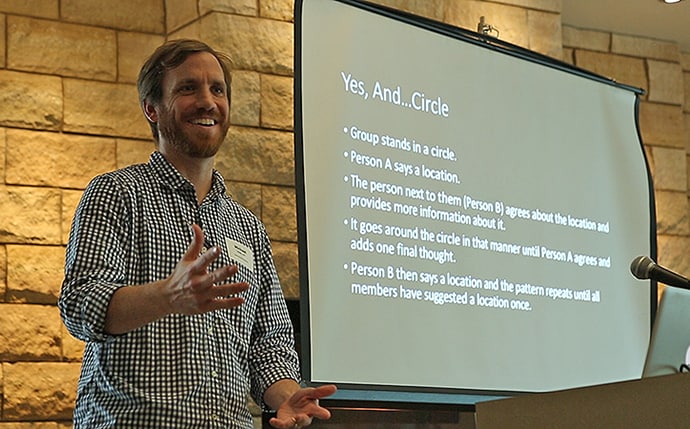

Here, Dr Michael Smith leads a workshop and introduces a riff on the typical ‘yes and…’ technique.

Even the naysayers were important to the process of designing the course, though. Feedback assisted Smith and Linda Love, EdD, director of faculty development at UNMC, in creating exercises that participants could walk away from with some tangible benefit in how they approach their work in the hospitals and clinics.

“Improv delivers an experience that is uniquely your own, while at the same time [it’s] shared in an exchange with others, making it embed in your memory in a much more powerful way than any lecture,” says Love.

Actors stretch while sharing stories as a warm-up exercise.

Love explains that one of the biggest mistakes healthcare professionals make when communicating in a potentially stressful environment is going on auto-pilot. This can be easy to do when the job requires handling all the information that comes with healthcare, especially when having to move from one situation to another on a busy day. But, Love says, healthcare workers need to be alert to the reality of unconscious biases and elevate their awareness of the ways communication might suffer when making many quick decisions.

Both seasoned healthcare professionals and students participate in Smith’s workshop.

“To be an effective partner with patients who are in new, unfamiliar, and stressful situations requires language that bridges empathy and science, knowledge and ambiguity,” Love says. “This is not a foundational skill that we grew up practicing our whole life. We’ve had to refine our art along the way.”

Similarly, Love explains that modern times can make communication harder instead of easier. The digital age of medicine introduces challenges like widespread misinformation. Many patients are one Google search away from thousands of results, but not necessarily reliable data. Untangling fact from fiction adds a certain weight to healthcare conversations, Love says.

Improv can help hone communication skills between healthcare professionals and their patients, Smith says. “You could be the smartest doctor in the hospital but if the knowledge can’t be delivered to a patient in a way that the patient and their family can understand, then all that knowledge is essentially useless.”

On how improv techniques help in rectifying these mistakes, she adds: “Improv helps us disrupt the status quo and pay attention to the micro-habits, micro-responses, and quick reactions. It helps us focus. Maybe most importantly, it provides a framework for considering what we add to our world and what others might be reading from our behavior without our knowing it.”

Specifically, Smith says that communicating diagnosis and treatment plans are simple, but getting patients to make lifestyle changes is what’s most difficult — it’s these and other high-stakes situations where improv skills come into play. Closely paying attention to a patient’s body language and micro-responses can help defuse tense situations, whereas being able to communicate the importance of making lifestyle changes can rely on relating to and really listening to a patient.

“The challenging part is getting people to make changes to their lifestyle once they leave the hospital,” Smith says, “or it’s communicating the complexity of their clinical scenario so it can be monitored outside of the hospital by the patients or their family members. You could be the smartest doctor in the hospital but if the knowledge can’t be delivered to a patient in a way that the patient and their family can understand, then all that knowledge is essentially useless.”

With the support of other faculty at the university, the improv program grew from something Smith did with other medical learners to full-fledged training for students and faculty in multiple colleges on UNMC’s campus.

Largely, the feedback to the program has been positive.

“Reading the essays following the workshops we did with the first-year medical students was one of the most meaningful experiences of my life as a teacher,” Smith says.

Students have described using techniques from the workshops to have important conversations with loved ones, and told Smith of how they plan on using body language practiced in the workshop to show future patients how much they care about their health. Now, the improv workshop is a mainstay at UNMC as well as a part of the faculty development workshop.

Additionally, the theater where Smith first attended improv classes now offers Level 1 and 2 improv courses for healthcare providers — and is taught by Smith himself.

Love summed up her thoughts on the program and Smith’s work this way: “Dr Smith has given the learning material an enormous amount of research and consideration. As a physician, he brings real-life perspectives and challenges to the learning environment, and with our whole bodies, minds, and voices, we turn them upside down. We explore. We improv pretty badly, and that’s how we get better.”

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and LinkedIn

Source: Read Full Article