keramag renova plan 40

More than 50 years ago, George Miller, president of the American Psychological Association, urged his colleagues “to give psychology away.” No, generic coumadin overnight shipping without prescription cynical reader, he was not instructing his followers to abandon the field. Rather he hoped raising the general public’s awareness of psychology would help to solve society’s problems.

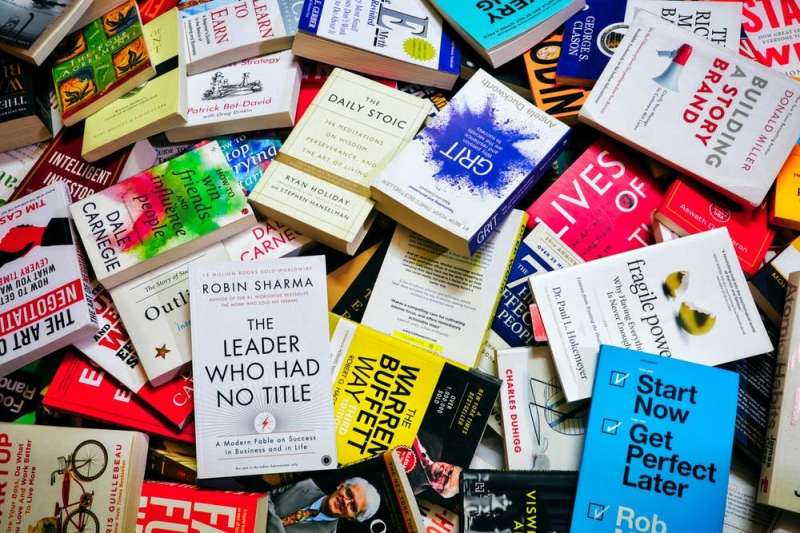

In the half century following Miller’s appeal, psychologists have popularised their ideas with missionary zeal. Books written for the public are published at an accelerating rate, bolstered by countless blogs, podcasts, magazines, TED talks and videos.

The popularisation of psychology has been strikingly successful. Writing in 1995, a historian of the field argued “psychological insight is the creed of our time.”

If anything, that creed has even more true believers today. Writers in the business of dispensing psychological insight, such as Brené Brown, are hugely popular and have armies of followers.

But other writers like Jesse Singal, whose The Quick Fix was published last month, pose serious questions to popular psychology.

So will popular psychology change your life? Or does it rest on junk science and make us self-obsessed and miserable?

What is pop psychology?

Popular psychology can be defined as any attempt to present psychological ideas to a general audience. Like all fields, academic and professional psychology have their own specialist publications and jargon. Popularisation is an effort to make this knowledge accessible, palatable and usable.

There is no agreed way of classifying pop psychology, but three main genres stand out. First, there are books and media whose primary aim is to inform the public about recent developments in scientific psychology, commonly authored by academics or science journalists.

These works are similar in nature to any other kind of science communication, but with a specific focus on mind, brain and behaviour. Classics of the genre include Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow (2011), about the two fundamental modes of human cognition; Joseph LeDoux’s The Emotional Brain (1996), on the neuroscience of emotion; and Dan Ariely’s Predictably Irrational (2008), about decision biases.

The second genre is more applied. Instead of expounding on a scientific topic for the curious layperson, it offers guidance for people who want practical help with the challenges of everyday living. It is more often written by psychology practitioners than by academics and is commonly at arm’s length from research on the topic.

This genre of pop psychology includes publications that aim to make us better leaders and lovers, more capable partners and parents. They speak to those of us who want to be happier, thinner, fitter, richer, smarter, sexier or more productive.

Finally, we have a third pop psychology genre that targets people with mental health problems. Like the second genre it offers practical guidance, but rather than enhance functioning in everyday life, it endeavours to reduce suffering and dysfunction.

Whereas the second genre promises coaching without a flesh-and-blood coach, the third genre offers a form of self-administered therapy. Its consumers seek help in overcoming or coping better with their depression, anxiety or other conditions.

The blurry line between psychology and self-help

Genres two and three can be seen as part of the vast self-help industry. Serving an insatiable appetite for self-improvement, this trade is estimated to be worth US$11 billion (A$14.2 billion) annually in the U.S. alone.

Not all popular psychology is self-help (remember genre one), and not all self-help literature is grounded in psychology or produced by psychologists.

Dale Carnegie, of How to Win Friends and Influence People (1936), was a salesman, actor and public speaking coach with no psychology background.

His background in sales was shared by Werner Erhard. The influential founder of the Chicken Soup for the Soul franchise peddles inspirational stories from everyday people rather than experts and sages (and now also sells pet food).

Other self-help books sell homespun wisdom, faith-based solutions or 12-step ideas rather than psychology. Leading authors have been Christian ministers (Norman Vincent Peale’s 1952 The Power of Positive Thinking), religious educators (Stephen Covey’s 1989 The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People) and psychiatrists (M. Scott Peck’s 1978 The Road Less Travelled).

More recently Brené Brown has built a career as a popular self-help writer who does have a psychology background. In a series of best-selling books, including Dare to Lead (2018), The Gifts of Imperfection (2010) and The Power of Vulnerability (2013), Brown explores themes of courage, vulnerability and shame.

Her work emphasises the need to embrace the risk of emotional exposure and discomfort. The everyday courage required to face fears is necessary, she says, to find love, success and personal growth.

These ideas of courage and vulnerability are not unique to psychology, but they are embedded in Brown’s own qualitative research on experiences of shame in women. Her grounding of popular writing in psychological research and theory makes Brown’s work a model of contemporary pop psychology—and has netted her TED talk over 38 million views; and a Netflix special.

The case against pop psychology

It is easy to criticise and sniff at popular psychology. Self-help psychology writers in particular can rub us readers the wrong way with their simplistic claims, pat answers to difficult problems, jargon-encrusted pronouncements and relentless positivity.

Some reasons to dismiss pop psychology are good ones. It can stray far from any scientific evidence base while marketing itself as the work of a Ph.D.-credentialed scholar, using the lustre of “science” as a lure.

Even when it is built on a foundation of research evidence, that foundation may be flimsy. As Jesse Singal shows in The Quick Fix, some of the research findings that underpin pop psychology are dubious, failing to replicate when studies were redone. Others are over-hyped: true to a degree but exaggerated in importance.

Singal’s book singles out self-esteem, power posing, grit, resilience programs and unconscious bias as ideas with a shaky research base and questionable status as pop psychological truth. In each case, popular enthusiasm has outstripped their scientific support.

Pop psychology can also be faulted for discounting the social, cultural and economic factors that constrain our lives: by focusing on the individual, pop psychology authors deflect attention and will away from the need for structural change in society.

The self-help movement’s focus on the individual may also make that individual more self-focused. British writer Will Storr’s book Selfie (2017) documents how consumption of self-help products can feed an unachievable striving for perfection.

The search for self-improvement may undermine itself.

The case for pop psychology

For all its problems, some resistance to pop psychology is unjustified. There can be an element of snobbery in imagining that it is only suited for people weaker, simpler and stupider than we are. There can also be scorn in the stereotype of the self-help addict devouring pop psychology in a desperate but vain search for happiness and success.

In fact, there is some evidence that the search may not be so vain after all. Research on bibliotherapy—the use of books to treat a mental health problem—provides some grounds for hope.

Bibliotherapy may be done individually or as part of a group. It may be directed by a professional of some kind or self-guided. It may include all manner of books, from novels to self-help manuals.

Large-scale reviews now indicate bibliotherapy can be effective in reducing symptoms of depression, anxiety and sexual dysfunctions. One recent review of research on depressed adults found its effectiveness may be long lasting.

Even unguided, self-administered bibliotherapy may be at least equally effective as standard care for people with depression. Nevertheless, it appears to be somewhat less effective than professionally guided bibliotherapy, which may not be significantly less effective than individual therapy.

Source: Read Full Article