Study finds large disparities in use of medications for opioid use disorder in pregnancy

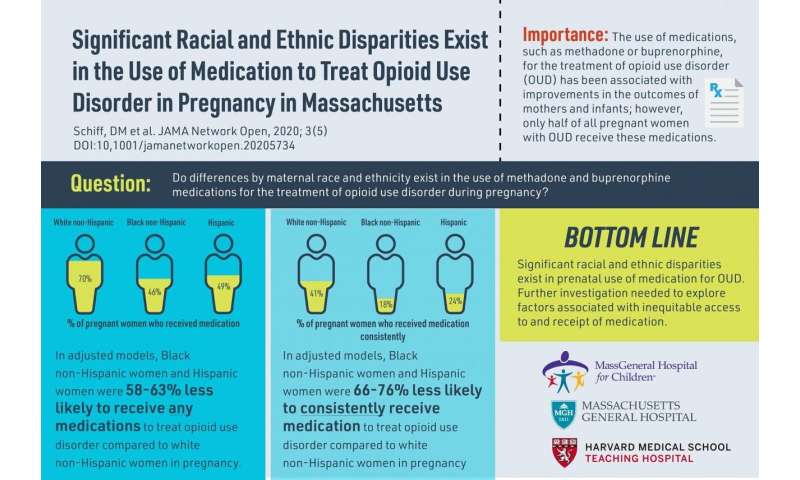

Black non-Hispanic and Hispanic women with opioid use disorder (OUD) are significantly less likely to receive or to consistently use any medication to treat their opioid use disorder during pregnancy than their white non-Hispanic counterparts, according to a new study from Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH).

Based on a population-level sample of women with OUD in the State of Massachusetts, the researchers found racial and ethnic disparities in the range of 60 to 75 percent, despite the fact use of the medications such as methadone and buprenorphine is associated with improvement in outcomes of both mothers and infants.

“We found evidence of striking racial and ethnic differences in terms of medication receipt, continuation of medication use, and type of medication received by pregnant women with OUD,” said Davida Schiff, MD, with the Division of General Academic Pediatrics, MassGeneral Hospital for Children, and lead author of the study, published in JAMA Network Open.

These findings have important implications for our healthcare system as opioid use disorder has increased four-fold over the past decade in the United States, mirroring the increased use of opioids in the general population.

The retrospective study by led by the MGH team and collaborators at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health is the first to explore racial/ethnic differences in the use of medication for OUD during pregnancy. Researchers examined a statewide cohort of more than 5,200 pregnant women with OUD from 2011 to 2015 (87 percent were white non-Hispanic).

They found that black women were 63 percent less likely and Hispanic women 58 percent less likely than white women to receive methadone (dispensed only in federally regulated methadone clinics) or buprenorphine (most commonly prescribed by physicians in office-based settings) for OUD while pregnant, after adjusting for other maternal characteristics.

Those disparities were even greater among women less than 25 years of age. The study further revealed that black non-Hispanic women were 76 percent less likely and Hispanic women 66 percent less likely than white non-Hispanic women to receive consistent treatment for more than six months prior to delivery.

Dr. Monica Bharel, MD, MPH, Commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (DPH) and co-author of the study, remarked that “data from our innovative Public Health Data Warehouse has enabled us to gain a deeper understanding of the opioid crisis and document inequities in treatment during pregnancy. This collaboration is an example of our data-driven approach to better understand the treatment experience for women of color and to improve outcomes for women and children.”

During pregnancy, medication along with behavioral therapy is recommended for the management for women with opioid use disorder. This regimen has been proven effective in adherence to prenatal care and in pregnancy outcomes, including lower rates of preterm birth and low birth weight, and reductions in maternal relapse and overdose.

And while pregnancy provides a motivational opportunity for women with OUD to initiate treatment and increase their engagement with health care services, the MGH study suggests that for all women, consistent use of medications during pregnancy in the second and third trimesters was low, at only 38 percent.

Yet for women of color, the rates were significantly lower. Deterrents may include increasingly punitive public policy toward pregnant women who use drugs, racial discrimination by clinicians, cultural differences around medication use, perceived stigma of drug use during pregnancy, and minimal social supports.

“Even in a state like Massachusetts which has a well-funded addiction treatment system and universal insurance coverage in pregnancy, we identified significant racial and ethnic disparities, suggesting that individual and systemic factors are discouraging women from receiving addiction treatment,” says Schiff, a pediatrician and medical director of the HOPE Clinic at MGH that cares for women and families with substance use disorders.

Source: Read Full Article