Cancer drugs cause large cells that resist treatment; scientist aims to stop it

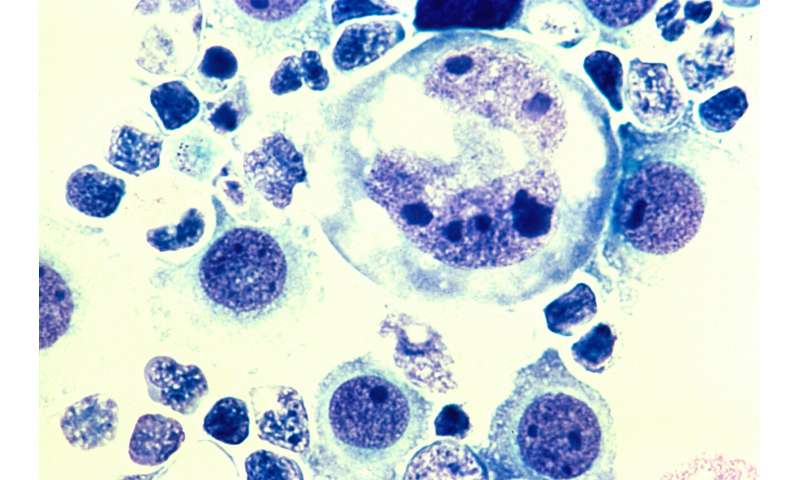

A cancer therapy may shrink the tumor of a patient, and the patient may feel better. But unseen on a CT scan or MR image, some of the cells are undergoing ominous changes. Fueled by new genetic changes due to cancer therapy itself, these rogue cells are becoming very large with twice or quadruple the number of chromosomes found in healthy cells. Some of the cells may grow to eight, 16 or even 32 times the correct number. Quickly, they will become aggressive and resistant to treatment. They will eventually cause cancer recurrence.

Daruka Mahadevan, MD, Ph.D., professor and chief of the Division of Hematology-Oncology in the Long School of Medicine at UT Health San Antonio, has studied this progression for 20 years. In a paper published in April 2020 in the journal Trends in Cancer, he and co-author Gregory C. Rogers, Ph.D., explain a rationale for stopping it.

“When you give therapy, some cells don’t die,” explained Dr. Mahadevan, leader of hematology and medical oncology care at the Mays Cancer Center, home to UT Health San Antonio MD Anderson. “These cells don’t die because they’ve acquired a double complement of the normal chromosomes plus other genetic changes. Many types of chemotherapy actually promote this.”

Dr. Mahadevan found that two cancer-causing genes, called c-Myc and BCL2, are operative in “double-hit” high-grade lymphomas, which are incurable. “These genes are part of the problem, because when they are present, they help the lymphoma cells to live longer and prime them to become large cells with treatment,” he said.

Although the drugs seem to be working, once therapy is stopped, the large rogue cells (called tetraploid cells) start to divide again and become smaller but faster-growing cells, driven by c-Myc and BCL2.

“It’s a double hit, a double whammy,” Dr. Mahadevan said.

To counter this, Dr. Mahadevan seeks to find drugs that prevent or treat the rogue cells’ acquisition of multiple chromosomes. He has identified a small-molecule inhibitor that shows promise in cell experiments in the laboratory. “We have data to show that it works,” he said.

Source: Read Full Article